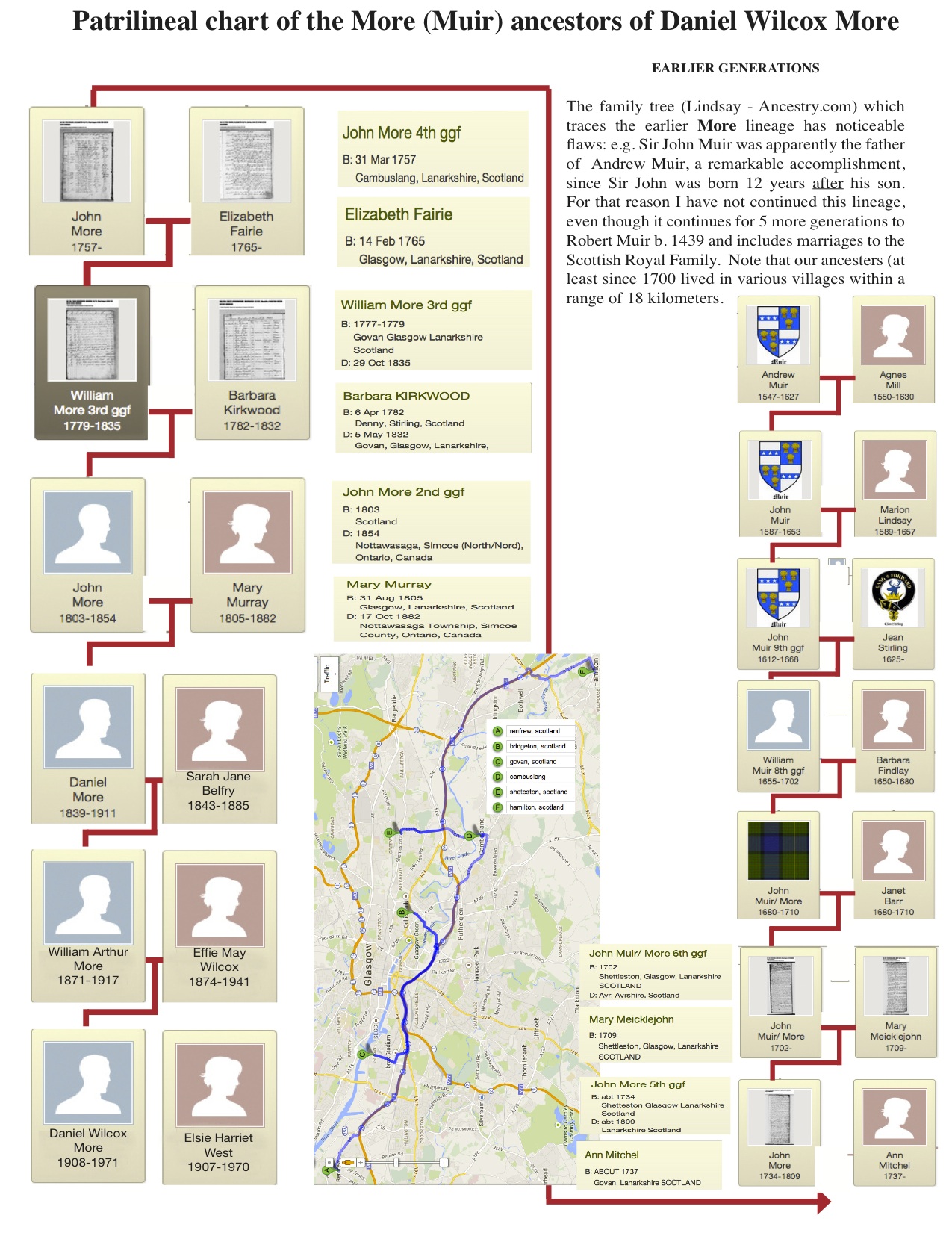

- More/Muir patrilineal chart

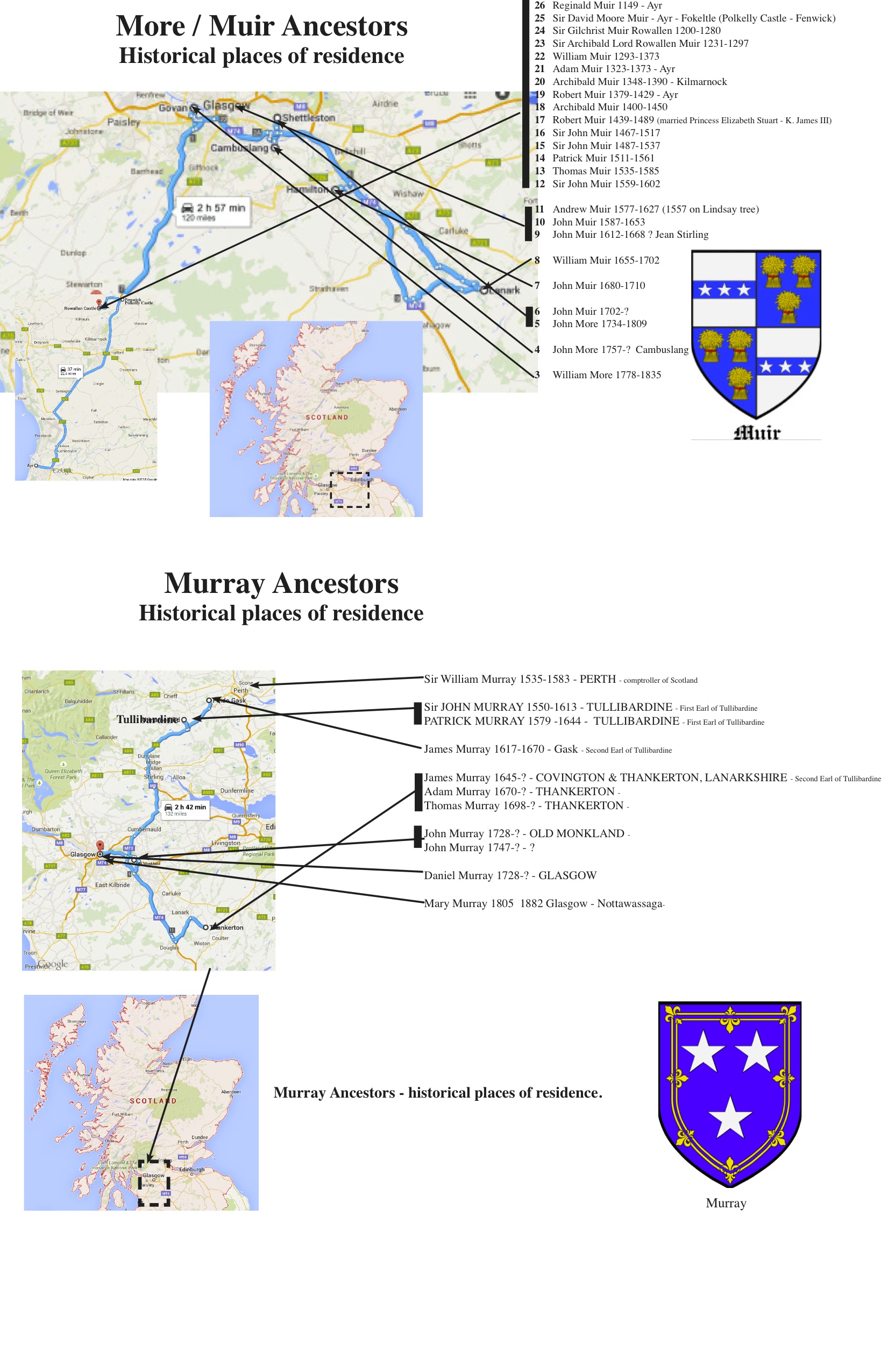

- More/Murray Places of Residence (When? / Where?)

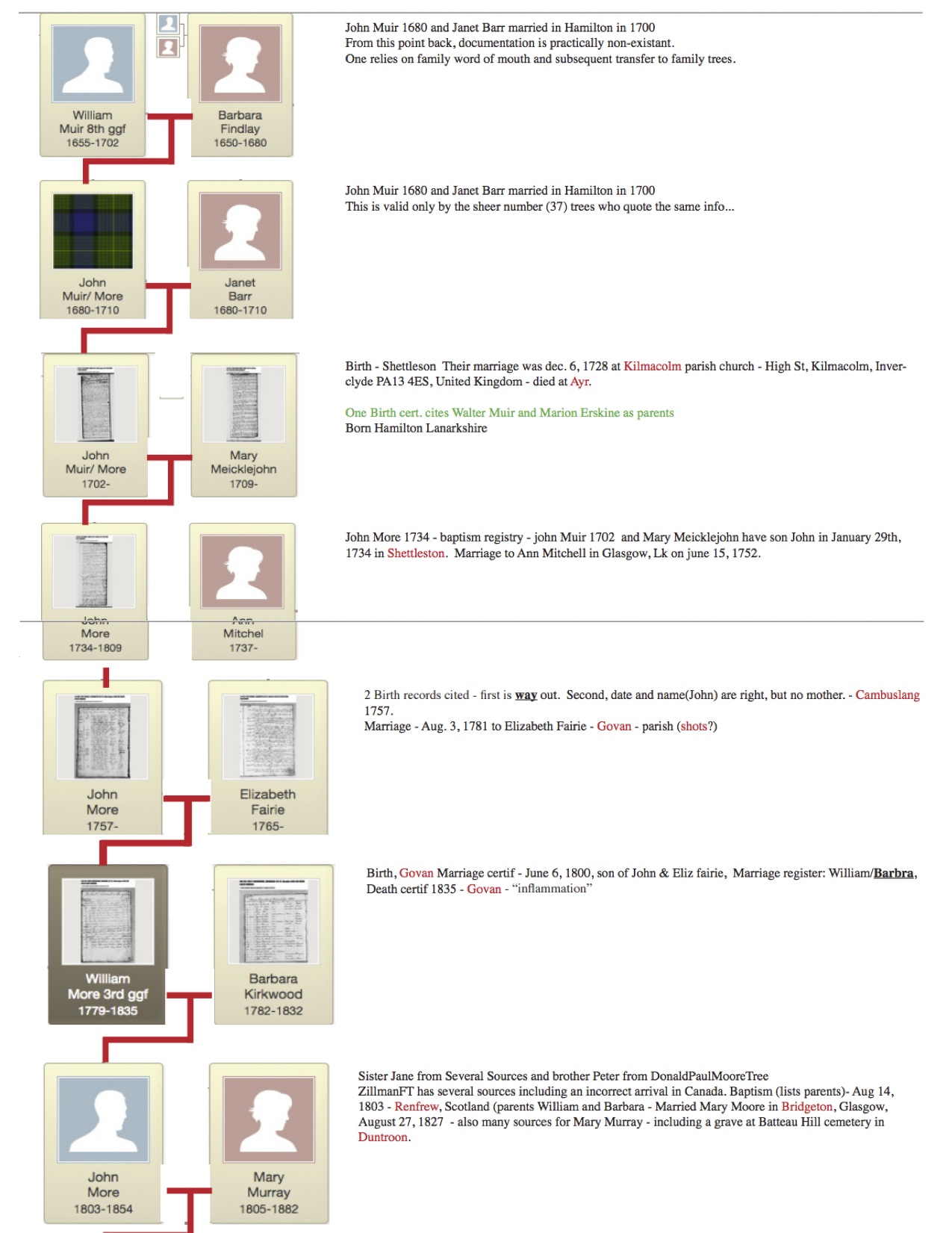

- More/Muir chronological data

- The Castles

- Scottish Emmigration and Reformation

- Scotland places to visit

- Scottish History Timeline

- Art’s Canada-Mores Family Chart

- Wilcox family ancestors back to the Plantagenets (10th C.) & Welsh royalty (9th C.)

- Sherman family ancestors back to the 12th C. AD.

- Befry Stories

- Belfry Book

Possible Day Trips:

- To Glasgow – (& other family sites) – visit Andrew McNaughton – 3 hours – 150 miles

- Ayr / Rowallen & Polkelly Castles / Lanark – 3 hours – 100 miles

- To Edinburgh – sight-seeing, archives & Dean Village – 4 hours – 160 miles

- Drive to the Highlands – Glencoe area – 5 hours – 250 miles

- Murray Lands – Perth – 3 hours – 100 miles

The Murrays

lived in the Castle here & in the area from 1535-1670

Tullibardine Chapel A9 ne from Stirling

A823 nnw at? past Gleneagles hotel- first right

Tullibardine Chapel is a monument to the piety of the powerful Murray family, ancestors of the dukes of Atholl. In 1446 Sir David Murray of Tullibardine and his lady, Margaret Colquhoun, founded a chantry chapel near their residence, Tullibardine Castle (demolished in the 1830s).

Their grandson, Sir Andrew Murray, substantially enlarged the chapel around 1500. This resulted in the present cross-shaped or cruciform plan and the squat bell tower.

A family mausoleum

The church lost its function as a private family chapel following the Protestant Reformation in 1560. But it continued in use as the family’s burial place into the 20th century.

Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s general, Lord George Murray, buried his infant daughter here in 1740. Lord George would have been interred at the same spot himself, had he not led the Jacobite army to defeat at Culloden in 1746 and been forced into permanent exile.

A moving place

The chapel is a real treasure – one of the few medieval churches in Scotland that survived the Reformation relatively unscathed. It is a moving place, sitting on its own within a neat, stone-walled graveyard dotted about with pines. To stand in its peaceful, darkened interior is to be transported back to the later Middle Ages.

The medieval timber roof remains complete, and niches for statues and aumbries (cupboards) for sacred vessels survive, minus their contents. The walls, inside and out, are studded with the coats of arms of the Murray family.

—————————–

For almost 500 years, (1149-1602) the Muirs (Mure/More) lived in South Eastern Scotland in Ayrshire., Polkelly Castle 1174-1500, Rowallan Castle, Kilmarnock

Fenwick, East Ayrshire, Scotland UK grid reference NS45684524 – a77 north past kilmarnock

Polkelly Castle

Polkelly Castle, also Pokelly, was an ancient castle located near Fenwick, at NS 4568 4524, in the medieval free Barony of Polkelly, lying north of Kilmarnock, Parish of Fenwick, East Ayrshire, Scotland. The castle is recorded as Powkelly (c1747), Pockelly (c1775), Pow-Kaillie, Ponekell, Polnekel, Pollockelly, Pollockellie, Pokellie, Pathelly Ha’[1] and Polkelly.[2] The name is given circa 1564 as Powkellie when it was held by the Cunninghams of Cunninghamhead.[3]

The Lands of Polkelly[edit]

Prior to the 1390s the evidence suggests that the lands of Polkelly were in the hands of the Comyns.[4] The estate was important to the Lairds of Rowallan as it gave uninhibited access to the large and important grazing lands of Macharnock Moor, now Glenouther Moor.[5]

In the charter of confirmation of 1512 the feudal Barony of Polkelly comprised Darclavoch, Clonherb, Clunch, with its mill, Le Gre, Drumboy, the lands of Balgray, with its tower, fortalice, manor, and mill, and the common of Mauchirnoch (Glenouther).[2] The Lainshaw Register of Sasines records that Laigh and High Clunch were part of the lands and barony of Pollockellie or Pokellie.[6]

Rowallen Castle

Reginald Muir 1149 – Ayr

Sir David Moore Muir – Ayr – Fokeltle (Polkelly Castle – Fenwick)

Sir Gilchrist Muir Rowallen 1200-1280

Sir Archibald Lord Rowallen Muir 1231-1297

William Muir 1293-1373

Adam Muir 1323-1373 – Ayr

Archibald Muir 1348-1390 – Kilmarnock

Robert Muir 1379-1429 – Ayr

Archibald Muir 1400-1450

Robert Muir 1439-1489 (married Princess Elizabeth Stuart – K. James III)

Sir John Muir 1467-1517

Sir John Muir 1487-1537

Patrick Muir 1511-1561

Thomas Muir 1535-1585

Sir John Muir 1559-1602

Rowallen Castle

The castle and barony has been owned or held by the medieval Muir family, the (Boyle) Earls of Glasgow, the (Campbell) Earls of Loudoun, the (Corbett) Barons Rowallan, and more recently by the developer, Niall Campbell.[2] It is said that the earliest piece of Lute music was written at Rowallan.[5] It is said to have been visited by the unfortunate King James I of Scotland when on his way from Edinburgh to England. The first Mure holder, Sir J. Gilchrist Mure was buried in the Mure Aisle at Kilmarnock.[6]

Origins[edit]

The original castle is thought to date back into the 13th century. Rowallan was said to be the birth place of Elizabeth Mure (Muir), first wife of Robert, the High Steward, later Robert II of Scotland.

In 1513 John Mure of Rowallan was killed at the Battle of Flodden. In 1513 the Rowallan Estate took its present day form.[7]

In about 1690 the estate was home to the Campbells of Loudoun, who held it into the 19th century.[7] The former tower of Polkelly lay near Rowallan and was also held by the Mures, for a time passed to the second son until it passed by marriage to the Cunninghams of Cunninghamhead.

Construction and other details[edit]

Rowallan Castle today

William Aiton’s map of 1811 showing Rowellan (sic)

The castle is built around a small knoll and once stood in a small loch or swampy area, fed by the Carmel Burn.[4] The southern front of the castle was erected about the year 1562 by John Mure of Rowallan and his Lady, Marion Cuninghame, of the family of Cuninghamhead. This information appears as an inscription on a marriage stone or tablet at the top of the wall: – Jon.Mvr. M.Cvgm. Spvsis 1562. The family coat of arms lies to the right. The crest of the Mure’s was a Moore’s head, which is sculptured near the coat of arms. This is no doubt a rebus or jeu-de-mot on the Mure name, however it is suggested that it is a reference to some feat performed in the crusades against the Saracens.[8] The Royal Arms of Scotland, fully blazoned, are carved over the main entrance, together with the shields of the Cumin family, from whom the Mures claim descent.[3] Over the ornamented gateway is a stone with the date 1616 inscribed upon it.[9]

Engraving of the castle by James Fittler in Scotia Depicta, published 1804

Over the doorway of the porch is an inscription in Hebrew using Hebrew characters which read The Lord is the portion of mine inheritance and of my cup, Psalms. XVI, Verse 5. Such an inscription is so rare as to be unique. Doctor Bonar, moderator of the Free church of Scotland, put much effort into deciphering and translating it.[10] At the front of the castle stood a perfect example of an old loupin-on-stane.[11] A fine well with abundant pure water was present at Rowallan.[12] King William’s well is located in the policies of Rowallan.[13]

One of the rooms was called Lord Loudoun’s sleeping apartment and Adamson records that almost every room throughout the house has its walls covered with the names and addresses of visitors. Some have also left poems or have recorded the details of their visit in verse.[14]

Sir John and Sir William Muir took great pleasure in the erection of the various parts of Rowallan, and a record was kept of the portions completed by each. Much of their attention was also taken up with the planting of the castle policies.[15]

Part of the castle was known as the ‘Womans House’ indicating the age when gender separation was the norm for the privileged classes, reflected in the decoration of these apartments and the sewing and other work undertaken by the ladies of the house.[16]

In 1691 the Hearth Tax records show that the castle had twenty-two hearths and eighteen other dwellings were associated with the castle and its lands.[17]

Dobie records that the Mures held Pow-Kaillie which extended to 2400 acres, two-thirds of which were arable.[7]

The origins of the lands of Polkelly and Rowallan as a unit may date back to the British period of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, as indicated by certain anomalies and coincidences in the boundaries of these lands.[8]

The castle[edit]

Polkelly became the secondary power centre within the feudal Barony of Rowallan. It became of minor importance when Balgray became the principal messuage of the free barony of Polkelly in 1512.[2] The castle lay close to the Balgray Mill Burn. The castle remains were removed in the 1850s and used to create a road, only leaving the motte, measuring 23m by 16m.[2]

Nearby Polkelly Castle and later Rowallan Castle (1300)

A Gulielmus (William) de Lambristoune was a witness to a charter conveying the lands of Pokellie (Pokelly) from Sir Gilchrist More to a Ronald Mure at a date around 1280. During the reign of Alexander III (1241–1286) Sir Gilchrist Mure held Pokelly and had to shelter there until the King was able to subdue Sir Walter Cuming. For the sake of peace and security Sir Gilchrist married his daughter Isabella to Sir Walter.[9]

In 1399 Sir Adam Mure held the castle and upon his death it passed to his second son, the eldest obtaining Rowallan. The lands of Limflare and Lowdoune Hill were included in the inheritance.[2] The castle and Barony of Polkelly was mainly held by the medieval Mure family, however Robert Mure of Polkelly had died by 1511, leaving his daughter Margaret, Lady Polkelly, as the sole heir.

Rowallen Castle – 1400 – 1600 (associated with Polkelly lands)

Muir clan

http://www.scotsconnection.com/clan_crests/Muir.htm

The Scottish Reformation

The Reformation in Scotland’s case culminated ecclesiastically in the re-establishment of the church along Reformed lines, and politically in the triumph of English influence over that of France. John Knox is regarded as the leader of the Scottish Reformation

The Reformation Parliament of 1560, which repudiated the pope’s authority, forbade the celebration of the mass and approved a Protestant Confession of Faith, was made possible by a revolution against French hegemony under the regime of the regent Mary of Guise, who had governed Scotland in the name of her absent daughter Mary, Queen of Scots, (then also Queen of France).

The Scottish Reformation decisively shaped the Church of Scotland[2] and, through it, all other Presbyterian churches worldwide.

A spiritual revival also broke out among Catholics soon after Martin Luther’s actions, and led to the Scottish Covenanters’ movement, the precursor to Scottish Presbyterianism. This movement spread, and greatly influenced the formation of Puritanism among the Anglican Church in England. The Scottish Covenanters were persecuted by the Roman Catholic Church. This persecution by the Catholics drove some of the Protestant Covenanter leadership out of Scotland, and into France and later, Switzerland.

John Knox

John Knox (c. 1513 – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish clergyman, theologian and writer who was a leader of the Protestant Reformation and is considered the founder of the Presbyterian denomination in Scotland. He is believed to have been educated at the University of St Andrews and worked as a notary-priest. Influenced by early church reformers such as George Wishart, he joined the movement to reform the Scottish church. He was caught up in the ecclesiastical and political events that involved the murder of Cardinal Beaton in 1546 and the intervention of the regent of Scotland Mary of Guise. He was taken prisoner by French forces the following year and exiled to England on his release in 1549.

While in exile, Knox was licensed to work in the Church of England, where he rose in the ranks to serve King Edward VI of England as a royal chaplain. He exerted a reforming influence on the text of the Book of Common Prayer. In England he met and married his first wife, Margery Bowes. When Mary Tudor ascended the throne and re-established Roman Catholicism, Knox was forced to resign his position and leave the country. Knox moved to Geneva and then to Frankfurt. In Geneva he met John Calvin, from whom he gained experience and knowledge of Reformed theology and Presbyterian polity. He created a new order of service, which was eventually adopted by the reformed church in Scotland. He left Geneva to head the English refugee church in Frankfurt but he was forced to leave over differences concerning the liturgy, thus ending his association with the Church of England.

On his return to Scotland he led the Protestant Reformation in Scotland, in partnership with the Scottish Protestant nobility. The movement may be seen as a revolution, since it led to the ousting of Mary of Guise, who governed the country in the name of her young daughter Mary, Queen of Scots. Knox helped write the new confession of faith and the ecclesiastical order for the newly created reformed church, the Kirk. He continued to serve as the religious leader of the Protestants throughout Mary’s reign. In several interviews with the Queen, Knox admonished her for supporting Catholic practices. When she was imprisoned for her alleged role in the murder of her husband Lord Darnley, and King James VI enthroned in her stead, he openly called for her execution. He continued to preach until his final days.

Emigration from Scotland

In 19th-century Scotland, emigration was the result of both force and persuasion. Until about 1855, a number of the emigrants from the Highlands were actually forced to leave the land because of evictions. In the Lowlands, the decision to move abroad was nearly always the outcome of the desire to improve one’s living standards. Whatever the reason, Scotland lost between 10% and 47% of the natural population increase every decade.

The scale of the loss was only greater in two other European countries: Ireland and Norway. However, even these countries were dwarfed by emigration from Scotland in the years 1904–1913, and again in 1921–1930, when those leaving (550,000) actually exceeded the entire natural increase and constitute

ed one-fifth of the total working population.

Leaving the Highlands

The eviction of Highlanders from their homes reached a peak in the 1840s and early 1850s. The decision by landlords to take this course of action was based on the fact that the Highland economy had collapsed, while at the same time the population was still rising.

As income from kelp production and black cattle dried up, the landlords saw sheep as a more profitable alternative. The introduction of sheep meant the removal of people. The crofting population was already relying on a potato diet and when the crop failed in the late 1830s and again in the late 1840s, emigration seemed the only alternative to mass starvation.

The policy of the landlord was to clear the poorest Highlanders from the land and maintain those crofters who were capable of paying rent. The Dukes of Argyll and Sutherland and other large landowners financed emigration schemes. Offers of funding were linked to eviction, which left little choice to the crofter. However, the Emigration Act of 1851 made emigration more freely available to the poorest.

The Highlands and Islands Emigration Society was set up to oversee the process of resettlement. Under the scheme a landlord could secure a passage to Australia for a nominee at the cost of £1. Between 1846 and 1857, around 16,533 people of the poorest types, mainly young men, were assisted to emigrate. The greatest loss occurred in the islands, particularly Skye, Mull, the Long Island and the mainland parishes of the Inner Sound.

Photograph of evicted Family, Lochmaddy, Outer Hebrides, 1895

After 1855, mass evictions were rare and emigration became more a matter of choice than compulsion. Between 1855 and 1895 the decline in the Highland population was actually less than in the rural Lowlands and certainly much lower than in Ireland. The Highlands experienced a 9% fall in population between 1851 and 1891, while Ireland in the same period faced a 28% fall. The Crofters’ Holding Act of 1886 gave the crofters security of tenure and this also slowed down the process of emigration. Between 1886 and 1950, over 2700 new crofts were created and a further 5160 enlarged.

However, despite the increase in the number of crofts, the exodus from the Highlands continued. In 1831, the population of the Highlands reached a peak of 200,955, or 8.5% of the total population of Scotland. In 1931, the comparable figures were 127,081 and 2.6%. In the west Highlands, for every 100 p

Places to Visit

Glasgow

– Trade and the Industrial Revolution

By the 16th century, the city’s trades and craftsmen had begun to wield significant influence and the city had become an important trading centre with the Clyde providing access to the city and the rest of Scotland for merchant shipping. The access to the Atlantic Ocean allowed the importation of goods such as American tobacco and cotton, and Caribbean sugar, which were then traded throughout the United Kingdom and Europe.

The de-silting of the Clyde in the 1770s allowed bigger ships to move further up the river, thus laying the foundations for industry and shipbuilding in Glasgow during the 19th century.

The abundance of coal and iron in Lanarkshire led to Glasgow becoming an industrial city. Textile mills, based on cotton and wool, became large employers in Glasgow and the local region.

Glasgow’s transformation from a provincial town to an international business hub was based originally on its control of the 18th-century tobacco trade with America. The trade was interrupted by the American Revolutionary War, and never recovered to even a fourth of its old trade. The tobacco merchants grew rich as their stocks of tobacco soared in value; they had diversified their holdings and were not badly hurt. Merchants turned their attention to the West Indies and to textile manufacture. The trade made a group of Tobacco Lords very wealth; they adopted the lifestyle of landed aristocrats, and lavished vast sums on great houses and splendid churches of Glasgow.[4] The merchants constructed spectacular buildings and monuments that can still be seen today, and reinvested their money in industrial development to help Glasgow grow further.

As the city’s wealth increased, its centre expanded westwards as the lush Victorian architecture of what is now known as the Merchant City area began to spring up. New public buildings such as the City Chambers on George Square, Trades Hall on Glassford Street, and the Mitchell Library in Charing Cross epitomised the wealth and riches of Glasgow in the late 19th century with their lavishly decorated interiors and intricately carved stonework. As this new development took place, the focus of Glasgow’s central area moved away from its medieval origins at High Street, Trongate, Saltmarket and Rottenrow, and these areas fell into partial dereliction, something which is in places still evident to the present day.

“Shipping on the Clyde”, by John Atkinson Grimshaw, 1881.

In 1893 the burgh was constituted as the County of the City of Glasgow. Glasgow became one of the richest cities in the world, and a municipal public transport system, parks, museums and libraries were all opened during this period.

Glasgow became one of the largest cities in the world, and known as “the Second City of the Empire” after London [although Liverpool, Dublin and several other British cities claim the same].[5] Shipbuilding on Clydeside (the river Clyde through Glasgow and other points) began when the first small yards were opened in 1712 at the Scott family’s shipyard at Greenock. After 1860 the Clydeside shipyards specialised in steamships made of iron (after 1870, made of steel), which rapidly replaced the wooden sailing vessels of both the merchant fleets and the battle fleets of the world. It became the world’s pre-eminent shipbuilding centre. Clydebuilt became an industry benchmark of quality, and the river’s shipyards were given contracts for warships.[6]

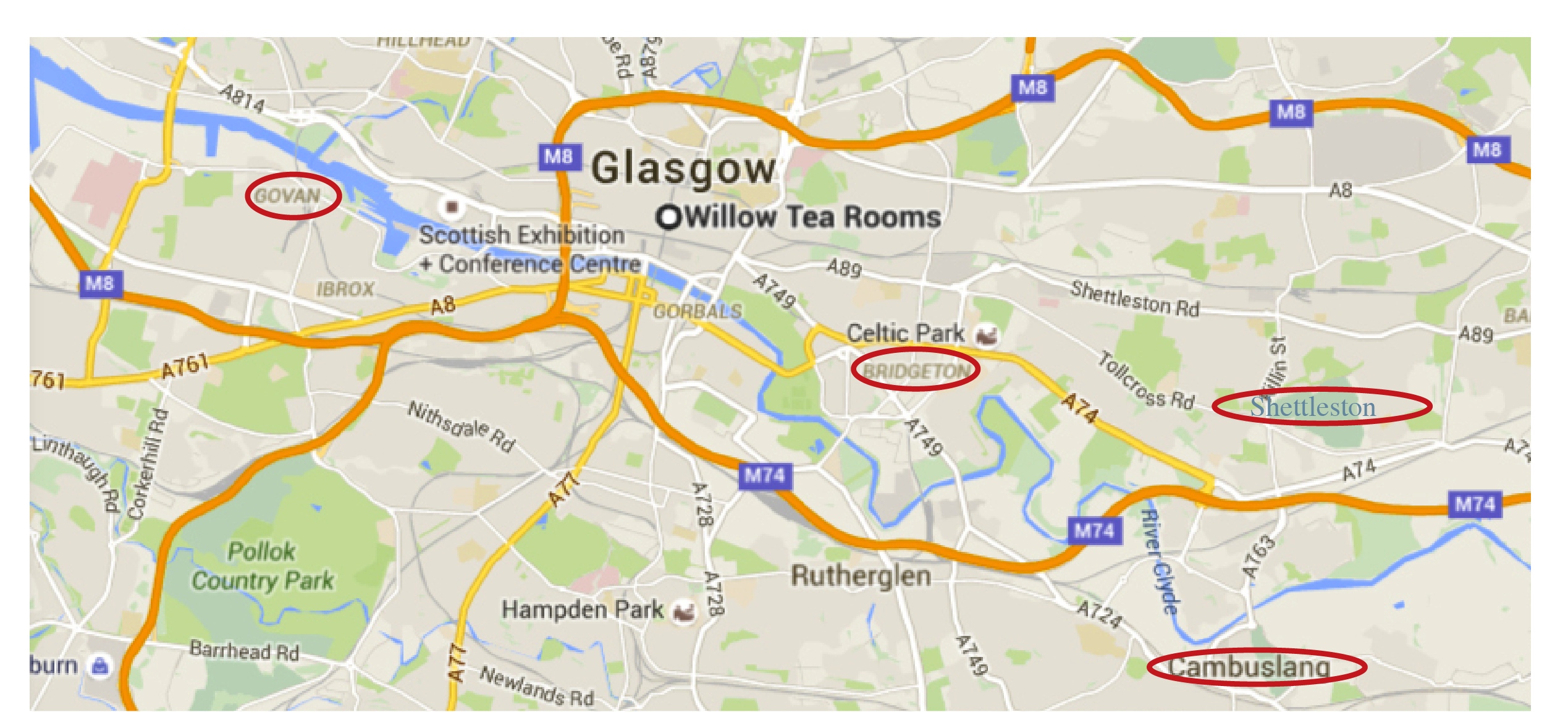

Govan

The former Parish of Govan was very large and covered areas on both banks of the Clyde. On the north side of the river, its boundary included Maryhill, Whiteinch, Partick, Dowanhill, Hillhead and Kelvinside. On the south side there was Govan, Ibrox, Kinning Park, Plantation, Huchesontown, Laurieston, Tradeston, Crosshill, Gorbals, Govanhill, West and East Pollokshields, Strathbungo and Dumbreck. xlvi This large area along both sides of the Clyde gives some indication of Govan‟s former importance as the royal home of the former kings of Strathclyde. During the 16th century, many families from outside the Parish were granted permission to settle in the lands at Govan. For instance, Maxwell of Nether Pollock settled in what is known today as the Pollock Estate. xlvii From the 16th until the 19th century, Govan was a coalmining district with pits in the Gorbals, Ibrox, Bellahouston, Broomloans, Helen Street, Drumoyne and at Craigton. These mines were finally closed near the end of the 19th century. Other industries during this time were salmon fishing, hand loom weaving, pottery, agriculture and silk making. Handloom weaving was introduced into Govan around 1800 although the Govan Weavers Society had been in existence since 1756. xlviii By 1839 there were 380 weavers in Govan who earned from 5 to 8 shillings a week. The silk mill was built in 1824 on the west side of Water Row before being demolished in 1901. xlix With the coming of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th centuries, the light industries tdisappeared and Govan became a shipbuilding town, with its first shipyard being the Old Govan Yard in 1839. l This was at the bottom of Water Row and it was only three years later that Robert Napier also built his yard facing the Old Govan one at Water Row. li Govan really came to the fore in the 19th century when it became a centre for heavy engineering works and shipbuilding. It was these industries that brought great prosperity to the town and with them came huge numbers of Highland and Irish migrants into the area. This caused the population to rise from just over 2,000 in 1830, to 92,000 people by 1912. By that time, Govan was part of Glasgow holding at least a dozen shipyards and numbers of associated heavy industries throughout the Parish. As Govan expanded new houses were needed for its growing population of workers which caused the old character, plan, and streets of the village to be mostly swept away and replaced with miles of tenement-lined streets. During the first half of the 20th century, Govan was known to the world as one of the best centers for ship-making and as an industrial manufacturing base.

Bridgeton

Unlike the West End of the city, which resulted from gradual urban expansion, the East End evolved from a series of small villages, Calton, Bridgeton, Shettleston, etc each with their roots as little weaving communities. As the local cottage industry was replaced by large scale powered mills, the East End of Glasgow became the city’s industrial powerhouse with the production of textiles at its core. Bridgeton, which prided itself as the world’s greatest engineering centre, was, for a short period in the early 20th Century, at the heart of Scotland’s blossoming motor car industry. Although the buildings of those original weaving communities have long since been swept away, the radical tradition of the weavers and pride in their heritage lives on. Contrary to popular opinion there is much of interest left and the visitor will be pleasantly surprised at some of the remarkable buildings on display here. Many outstanding local architects played their part in the construction of the fine buildings and monuments featured on the heritage trail, the bulk of which were erected during the rapid expansion of the industrial period of the last century. Despite some unseemly alterations, and the accumulated pollution and grime of the passing years, the quality of their original design still shines through.

History of Shettleston

A Papal Bull of 1179 addressed to the Bishop of Glasgow refers to “villam filie Sedin” – the residence of Sedin’s son or daughter, and a later reference records a “Schedinestun”, a place name which throughout the Middle Ages appears in the rental book of the diocese of Glasgow spelt in 48 different ways.

A charter granted by Alexander II in 1226 to the Bishop of Glasgow prohibited the provost, baillies and officers of Rutherglen taking toll or custom in Glasgow but permitting legal dues to be collected at “the cross of Shedenestun”.

Most authorities seems to agree that the “Schedenestun” in such old records is the place now known as Shettleston, although the site of “the cross of Schedenestun” may not be the location of what in modern times became known as Shettleston Cross.

However, it has also been said that being an old weaving village, the name was derived from “Shuttles-town”, and there are records with this spelling of the name. In Ross’s map of Lanarkshire of 1773 it is spelt “Shuttleston”, and the parish church has in its possession five pewter communion vessels each inscribed “Shuttlestoun Kirk – 1783.”

Both derivations of the name seem acceptable, the ancient form of “Schedinestun” becoming over the centuries the modern Shettleston, whilst “Shuttlestoun” was more probably the colloquial pronunciation of the name in the local dialect at the end of the 19th century and is not too unlike the way it is pronounced by some older residents even to this day.

Although a church was built at Eastmuir in 1752, initially it was only a preaching station and Shettleston did not become a separate parish until 1847. Consequently in the Statistical Account of 1795 there is only a brief reference to the building of houses to accommodate two to six families in the thriving villages of Shettleston and Middle Quarter, which at that period had a joint population of 766 inhabitants.

At the start of the 19th century and for the next hundred years Shettleston could be described as a group of four small and separate villages with the farmland stretching northwards to the Monkland Canal and to the village of Tollcross to the south. From the west Low Carntyne ran from the Sheddings to Wellshot Road, Old Shettleston from Wellshot Road to McNair Street, then Middle Quarter from McNair Street to Annick Street, Eastmuir from Annick Street to Fingask Street and then Sandyhills (not the housing scheme) running eastwards to Barrachnie.

Pigot’s Commercial Directory of 1837 records Shettleston as a considerable village situated on the high road from Glasgow to Edinburgh chiefly inhabited by weavers and through which passed six stage coaches per day bound for Edinburgh – the “Express” at 6.00am, the “Telegraph” at 9.45am, the “Regulator” at 12 noon, the “Enterprise” at 4.00pm, the “Red Rover” at 5.45 pm, and the “Royal Mail” at 10.30pm.

Coal was mined in the area as far back as 1600, and the Grays of Carntyne and the McNairs of Greenfield owned and operated coal-mines in the area over several generations, and together with the Dunlops of Tollcross who established the Clyde Iron Works in 1786, were mainly responsible for the introduction of heavy industry into this rural area.

History of Cambuslang

The town is located just south of the River Clyde and about 6 miles (10 km) south-east of the centre of Glasgow. It has a long history of coal mining, iron and steel making, and ancillary engineering works, most recently Hoover. Tata Steel Europe’s Clydebridge Steel Works and other smaller manufacturing businesses continue but most employment in the area comes from the distribution or service industries.

Cambuslang is an ancient part of Scotland where Iron Age remains loom over 21st century housing developments. The local geography explains a great deal of its history. It has been very prosperous over time, depending first upon its agricultural land, (supplying food, then wool, then linen), then the mineral resources under its soil (limestone and coal, and, to some extent, iron). These were jealously guarded by the medieval Church, and later by the local aristocracy, particularly the Duke of Hamilton (previously Barons of Cadzow and Earls of Arran).

Because of its relative prosperity, Cambuslang has been intimately concerned in the politics of the country (through the Hamilton connection) and of the local Church. Bishop John Cameron of Glasgow, the Scottish King James I’s first minister, and Cardinal Beaton, a later first minister, were both Rectors of Cambuslang. This importance continued following the Protestant Reformation. From then until the Glorious Revolution a stream of Ministers of Cambuslang came, were expelled, or were re-instated, according to whether supporters of the King, Covenanters, or Oliver Cromwell were in power. The religious movements of the 18th century, including the Cambuslang Wark, were directly linked to similar movements in North America. The Scottish Enlightenment was well represented in the person of Rev Dr James Meek, the Minister. His troubles with his parishioners foreshadowed the split in the Church of Scotland during the 19th century.

The manufacturing industries that grew up from the agricultural and mineral resources attracted immigrants from all over Scotland and Ireland and other European countries. Cambuslang benefited at all times from its closeness to the burgeoning city of Glasgow, brought closer in the 18th century by a turnpike road then, in the 19th century, by a railway. In the 21st century, it continues to derive benefit from its proximity to Glasgow and to wider communication networks, particularly via the M74 motorway system.

New Lanark Mill

New Lanark – Cotton Mill – contained society

Robert Owen, a Welsh philanthropist and social reformer, New Lanark became a successful business and an epitome of utopian socialism as well as an early example of a planned settlement and so an important milestone in the historical development of urban planning.[1]

Hamilton

The town of Hamilton was originally known as Cadzow or Cadyou[2] (Middle Scots: Cadȝow, the “ȝ” being the letter yogh), pronounced /kadyu/. During the Wars of Scottish Independence the Hamilton family initially supported the English and Walter fitz Gilbert (the head of the Hamilton family) was governor of Bothwell Castle on behalf of the English. However, he later changed loyalty to Robert the Bruce, following the Battle of Bannockburn, and ceded Bothwell to him. For this act, he was rewarded with a portion of land which had been forfeited by the Comyns at Dalserf and later the Barony and lands of Cadzow, which in time would become the town of Hamilton.

Cadzow was renamed Hamilton in the time of James, Lord Hamilton, who was married to Princess Mary, the daughter of King James II. The Hamilton family themselves most likely took their name from the lands of Humbleton or Homildon in Northumberland, or perhaps from a place near Leicester.[3]

The Hamiltons constructed many landmark buildings in the area including the Hamilton Mausoleum in Strathclyde Park, which has the longest echo of any building in the world. The Hamilton family are major land-owners in the area to this day. Hamilton Palace was the seat of the Dukes of Hamilton until the early-twentieth century.

Other historic buildings in the area include Hamilton Old Parish Church, a Georgian era building completed in 1734 and the only church to have been built by William Adam. The graveyard of the old parish church contains some Covenanter remains. The former Edwardian Town Hall now houses the library and concert hall. The Townhouse complex underwent a sympathetic modernization in 2002 and opened to the public in summer 2004. The ruins of Cadzow Castle also lie in Chatelherault Country Park, 2 miles (3 km) from the town centre.

Edinburgh

The royal burgh was founded by King David I in the early 12th century on land belonging to the Crown, though the precise date is unknown.[23] By the middle of the 14th century, the French chronicler Jean Froissart was describing it as the capital of Scotland (c.1365), and James III (1451–88) referred to it in the 15th century as “the principal burgh of our kingdom”.[24] Despite the destruction caused by an English assault in 1544, the town slowly recovered,[25] and was at the centre of events in the 16th-century Scottish Reformation[26] and 17th-century Wars of the Covenant.[27]

17th century[edit]

Edinburgh in the 17th century

In 1603, King James VI of Scotland succeeded to the English throne, uniting the crowns of Scotland and England in a personal union known as the Union of the Crowns, though Scotland remained, in all other respects, a separate kingdom.[28] In 1638, King Charles I’s attempt to introduce Anglican church forms in Scotland encountered stiff Presbyterian opposition culminating in the conflicts of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.[29] Subsequent Scottish support for Charles Stuart’s restoration to the throne of England resulted in Edinburgh’s occupation by Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth of England forces – the New Model Army – in 1650.[30]

In the 17th century, the boundaries of Edinburgh were still defined by the city’s defensive town walls. As a result, expansion took the form of the houses increasing in height to accommodate a growing population. Buildings of 11 storeys or more were common,[31] and have been described as forerunners of the modern-day skyscraper.[32] Most of these old structures were later replaced by the predominantly Victorian buildings seen in today’s Old Town.

18th century[edit]

In 1706 and 1707, the Acts of Union were passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland uniting the two kingdoms into the Kingdom of Great Britain.[33] As a consequence, the Parliament of Scotland merged with the Parliament of England to form the Parliament of Great Britain, which sat at Westminster in London. The Union was opposed by many Scots at the time, resulting in riots in the city.[34]

By the first half of the 18th century, despite rising prosperity evidenced by its growing importance as a banking centre, Edinburgh was being described as one of the most densely populated, overcrowded and unsanitary towns in Europe.[35][36] Visitors were struck by the fact that the various social classes shared the same urban space, even inhabiting the same tenement buildings; although here a form of social segregation did prevail, whereby shopkeepers and tradesmen tended to occupy the cheaper-to-rent cellars and garrets, while the more well-to-do professional classes occupied the more expensive middle storeys.[37]

A painting showing Edinburgh characters (based on John Kay’s caricatures) behind St Giles’ Cathedral in the late 18th century

During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Edinburgh was briefly occupied by the Jacobite “Highland Army” before its march into England.[38] After its eventual defeat at Culloden, there followed a period of reprisals and pacification, largely directed at the rebellious clans.[39] In Edinburgh, the Town Council, keen to emulate London by initiating city improvements and expansion to the north of the castle,[40] re-affirmed its belief in the Union and loyalty to the Hanoverian monarch George III by its choice of names for the streets of the New Town, for example, Rose Street and Thistle Street, and for the royal family: George Street, Queen Street, Hanover Street, Frederick Street and Princes Street (in honour of George’s two sons).[41]

In the second half of the century, the city was at the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment,[42] when thinkers like David Hume, Adam Smith, James Hutton and Joseph Black were familiar figures in its streets. Edinburgh became a major intellectual centre, earning it the nickname “Athens of the North” because of its many neo-classical buildings and reputation for learning, similar to Ancient Athens.[43] In the 18th century novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker by Tobias Smollett one character describes Edinburgh as a “hotbed of genius”.[44]

From the 1770s onwards, the professional and business classes gradually deserted the Old Town in favour of the more elegant “one-family” residences of the New Town, a migration that changed the social character of the city. According to the foremost historian of this development, “Unity of social feeling was one of the most valuable heritages of old Edinburgh, and its disappearance was widely and properly lamented.”[45]

Stirling was originally a Stone Age settlement as shown by the Randolphfield standing stones and Kings Park prehistoric carvings that can still be found south of the town.[3][4] The city has been strategically significant since at least the Roman occupation of Britain, due to its naturally defensible crag and tail hill (latterly the site of Stirling Castle), and its commanding position at the foot of the Ochil Hills on the border between the Lowlands and Highlands, at the lowest crossing point of the River Forth. It remained the river’s lowest crossing until the construction of the Kincardine Bridge further downstream in the 1930s. It is supposed that Stirling is the fortress of Iuddeu or Urbs Giudi where Oswiu of Northumbria was besieged by Penda of Mercia in 655, as recorded in Bede and contemporary annals.

A ford, and later bridge, of the River Forth at Stirling brought wealth and strategic influence, as did its port. The town was chartered as a royal burgh by King David in the 12th century, with charters later reaffirmed by later monarchs (the town then referred to as Strivelyn). Major battles during the Wars of Scottish Independence took place at the Stirling Bridge in 1297 and at the nearby village of Bannockburn in 1314 involving William Wallace and Robert the Bruce respectively. There were also several Sieges of Stirling Castle in the conflict, notably in 1304. Sir Robert Felton, governor of Scarborough Castle in 1311, was slain at Stirling in 1314.

Stirling

The origin of the name Stirling is uncertain, but folk etymology suggests that it originates in either a Scots or Gaelic term meaning the place of battle, struggle or strife. Other sources suggest that it originates in a Brythonic name meaning “dwelling place of Melyn”.[5] The town has two Latin mottoes, which appeared on the earliest burgh seal of which an impression of 1296 is on record:[6]

Hic Armis Bruti Scoti Stant Hic Cruce Tuti (The Britons stand by force of arms, The Scots are by this cross preserved from harms) and

Continet Hoc in Se Nemus et Castrum Strivilinse (The Castle and Wood of Stirling town are in the compass of this seal set down.)

Standing near the castle, the Church of the Holy Rude is one of the town’s most historically important buildings. Founded in 1129 it is the second oldest building in the city after Stirling castle. It was rebuilt in the 15th century after Stirling suffered a catastrophic fire in 1405, and is reputed to be the only surviving church in the United Kingdom apart from Westminster Abbey to have held a coronation.[7] On 29 July 1567 the infant son of Mary, Queen of Scots, was crowned James VI of Scotland here.[7] Musket shot marks that may come from Cromwell’s troops during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms are clearly visible on the tower and apse.[7] Another important historical religious site in the area is the ruins of Cambuskenneth Abbey, the resting place of King James III of Scotland and his queen, Margaret of Denmark.[8] During the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, the Battle of Stirling also took place in the centre of Stirling on 12 September 1648.

The tomb of James III, King of Scots at Cambuskenneth Abbey

The fortifications continued to play a strategic military role during the 18th century Jacobite Risings. In 1715, the Earl of Mar failed to take control of the castle. On 8 January 1746 (OS) 19 January 1746 (NS), the army of Bonnie Prince Charlie seized control of the town but failed to take the Castle. On their consequent retreat northwards, they blew up the church of St. Ninians where they had been storing munitions; only the tower survived and can be seen to this day.[9]

Economically, the city’s port supported overseas trade, including tea trade with India and timber trade with the Baltic. The coming of the railways in 1848 started the decline of the river trade, not least because a railway bridge downstream restricted access for shipping. By the mid 20th century the port had ceased to operate.

Perth

Perth was made a town or burgh by King David I in the early 12th century. There was probably already a settlement there but it was an obvious place to create a new town. It was at the first spot where the River Tay could be bridged. On the other hand ships could easily sail up the river to Perth. In the Middle Ages Perth was a busy inland port. Hides, timber and fish were exported. Perth was also a manufacturing center. Wool was woven in Perth. It was then fulled. That means it was beaten in a mixture of water and clay to thicken and clean it. At first the wool was trodden into the water and clay by human feet. (The men who did this were called walkers). Later the wool was pounded by wooden hammers worked by watermills. There was also a leather industry in Medieval Perth. There were skinners and tanners and leather was used to make things like gloves and shoes. There were also horners. In the Middle Ages cow and goat horn was used to make things like spoons, combs and ink wells. There were also the same craftsmen found in any medieval town like butchers, bakers and blacksmiths. In the Middle Ages Perth had weekly markets. It also had annual fairs. In the Middle Ages fairs were like markets but they were held only once a year and they attracted buyers and sellers from a wide area. In 1231 Dominican friars came to Perth. In the Middle Ages friars were like monks but instead of withdrawing from the world they went out to preach and help the poor. Dominicans were known as black friars because of their black costumes. Carmelites of white friars came to Perth in 1260. Franciscans or grey friars came to Perth in 1460. In 1429 a small monastery was founded for Carthusian monks. During the Middle Ages the only ‘hospitals’ were run by the church. In Perth there were 5 hospitals. In them monks looked after the sick and the poor as best they could. (They also provided hospitality for poor travelers). There was also a leper hostel outside the town. In 1210 Perth was severely damaged by floods. However the town recovered and King William the Lion made it a royal burgh. At first Perth was probably defended by a ditch and an earth rampart with a wooden palisade on top. However Perth was occupied by the English from 1296 to 1313. In 1304 the English king ordered that stone walls be built around Perth. However when the Scots re-captured Perth in 1313 they destroyed these walls to prevent the English occupying Perth again. In 1329 Robert the Bruce was succeeded by his 5 year old son. In 1332 Edward Balioll, the son of King John landed in Fife with his supporters. They fought a battle against the regent at Musselburgh. Balioll captured Perth and he was crowned king of Scotland. Civil war followed. Balioll’s forces held Perth until 1339, with English support. It was relatively easy for them to hold Perth because it was a port. Perth could be supplied water. In 1396 came the battle of the clans. There are different versions of what happened. Two clans or federations of clans were feuding and the king asked them to settle their differences by choosing 30 champions who would fight each other. The two sides fought on North Inch. One side, the Mackays, were left with just one survivor who fled by swimming across the Tay. King James I was assassinated by nobles in Perth in 1437. In January the King and Queen were staying in the black friary. At midnight rebels led by Robert Graham broke into his rooms and stabbed him 16 times. The Queen and her children escaped to Edinburgh. PERTH IN THE 16th CENTURY AND 17th CENTURY Perth was one of the birthplaces of the Scottish Reformation. In 1544 6 people were executed in Perth for heresy. However in 1559 John Knox made a rousing sermon in St Johns Kirk. He claimed that the mass was idolatry. The audience responded by smashing the high altar. They then went on to destroy the friaries and monasteries. Following the reformation St Johns Kirk was divided into 3 separate kirks. In 1600 came the Gowrie conspiracy. According to King James VI he was hunting at Falkland when the Earl of Gowrie’s brother, Alexander Ruthven asked him to come to Gowrie House. Ruthven supposedly told the king that they had a man with a container of foreign coins at the house. The king eventually went with a group of companions. The king was led to a room in a turret by Ruthven who then locked the door. According to the king, Ruthven then threatened him with a dagger. Ruthven left the room and locked the door. Meanwhile the companions of the king were told that the king had left and they were about to leave as well. However the king opened a window and called for help. The kings companions rushed to the room and killed Ruthven. The Earl of Gowrie then rushed to the scene with his servants and in the ensuing fight he was killed. It is believed by many that the conspiracy was stage managed by the king to get rid of a family he disliked. In the 16th century and the 17th century there a number of metalworkers in Perth. As well as blacksmiths there were goldsmiths and silversmiths and craftsmen who worked with pewter. There were also armourers (armour makers) and, when guns became common, gunsmiths. The leather industry continued to prosper. There were also weavers and fullers in Perth. Furthermore Perth was still a busy little port. However in the late 17th century a linen industry grew up in Perth. It soon became the pillar of the town’s prosperity. By the late 16th century Perth probably had a population of around 6,000. By the standards of the time it was a large town. Like all towns in those days Perth suffered from outbreaks of plague. It struck in 1512, 1585-87 and again in 1608 and 1645. However each time the plague struck the town recovered and it continued to slowly grow larger. James VI’s hospital was built in 1569. (The present building is mid-18th century). A new bridge was built across the Tay in 1616 but it only lasted for 5 years. It was destroyed by severe storms and flooding. The Fair Maid’s House dates from the early 17th century. In 1644 the royalist Marquis of Montrose captured Perth after he won the battle of Tippermuir. Charles II was crowned king at Scone in 1651. However in August 1651 an English army captured Perth. Cromwell built a fort on South Inch but it was demolished in 1661.

Scottish History Timeline

1100s The Kingdom of Alba emerges. David I (around 1080 – 1153) is responsible for transforming Scotland into a feudal kingdom, modelled in part on its neighbour to the south. Scotland’s relationship with England is to play an integral role in its subsequent history

1296 Edward I of England invades Scotland.

1297 William Wallace and Andrew de Moray raise forces to resist the occupation. Together they defeat an English army at the Battle of Stirling Bridge.

1298 Wallace is defeated by Edward I at the Battle of Falkirk

1305 Wallace is executed by the English for treason, which he denies stating that he had never sworn allegiance to the English king

1306 Robert the Bruce is crowned King of Scotland

1307 Edward I dies

1314 Robert the Bruce and his army defeat Edward II and the English army at the Battle of Bannockburn securing de facto independence

1320 The Declaration of Arbroath is sent to Pope John XXII and proclaims Scotland’s status as an independent sovereign state. The declaration is regarded as one of the most important documents in Scottish history and is believed to have inspired Thomas Jefferson when writing the American Declaration of Independence.

1328 The Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton is signed by Robert I and Edward III recognising Scotland’s independence under the rule of Robert the Bruce

1494-5 King James IV grants a commission to Friar John Cor, a monk at Lindores Abbey in Fife, to make acqua vitae (whisky) – the earliest official record of distilling in Scotland

1513 Scotland’s alliance with France – the Auld Alliance – brings disaster. During the Battle of Flodden against the English army, King James IV’s army suffers a devastating defeat with more than 10,00 men killed including the king himself

1559 John Knox delivers his fiery sermon against idolatry at St John’s Kirk in Perth which fans the flames of the Protestant Reformation in Scotland

1560 The Papal Jurisdiction Act is passed by the Scottish Parliament which declares that the Pope has no jurisdiction in Scotland

1587 The Catholic Mary Queen of Scots is executed on the orders of Elizabeth I

1603 The union of the crowns makes James VI of Scotland also James I of England. The kingdoms of England and Scotland become sovereign states with their independent parliaments, judiciary and legal systems

1638 The National Covenant of Scotland is formed in opposition to the religious policies of Charles I. This revolt triggers civil insurrection in Ireland and then England

1639-40 Charles I attempts to impose an Episcopalian system of religious governance upon Scotland. This is rejected by the country’s Presbyterian majority. A series of military and political conflicts ensue which become known as the Bishops’ Wars

1644-45 A Scottish civil war between Scottish Royalists – supporters of Charles I – and Covenanters who have controlled Scotland since 1639 and are allied to the English Parliament is fought. Aided by Irish troops, the Scottish Royalists enjoy a series of early victories but are ultimately defeated

1646 Charles I surrenders to the Scottish Covenanter army in England bringing an end to the first English Civil War

1649 Charles I is executed following a trial for treason, called by a rump of radical MPs

1650 The Kirk Party insists the new king should accept the covenant and establish a Presbyterian church government in the three kingdoms. Charles II is obliged to sign the Treaty of Breda

1651 Oliver Cromwell’s Republican forces defeat the Scots at the Battle of Inverkeithing before terminating the Royalist-Covenanter alliance and eventually defeating the King at Worcester

1651-54 Royalist uprisings spread across Scotland. Dunnottar Castle is the last stronghold to fall to the English Parliament’s troops in May 1652. General George Monck garrisons forts across the Highlands to suppress Royalist resistance

1658 Oliver Cromwell dies

1660 Charles II returns from exile and the monarchy is restored

1668 The Glorious Revolution takes place. The catholic James II is replaced by the joint monarchy of his protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange.

1707 The Act of Union of 1707 merges England and Scotland into a single state of Great Britain, creating a single parliament at Westminster. The union put an end to Jacobite hopes of a Stuart restoration by ensuring the German Hanoverian dynasty succeeded Queen Anne upon her death – but the Stuarts still commanded loyalty in Scotland, France and England

1708 James Francis Edward Stuart, the son of James VII, who becomes known as the ‘Old Pretender’, attempts an invasion with a French fleet carrying 6,000 men, but the Royal Navy prevents it from landing

1715 The Earl of Mar leads the second Jacobite rising which is eventually quashed at the Battle of Preston

1745 The final Jacobite rising begins. Charles Edward Stuart, also known as Bonnie Prince Charlie or the Young Pretender, lands on the Isle of Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides. With the support of several clans, he successfully captures Edinburgh and defeats the only government army in Scotland at the Battle of Prestonpans

1746 The Jacobites are crushed by the forces of the Duke of Cumberland at Culloden. This defeat signals the demise of the Jacobite cause. With the aid of the Highlanders, Charles flees to Skye and returns to France where he spends the rest of his life in exile

Post-1746 The military catastrophe of Culloden heralds the collapse of the clan system. A number of laws are introduced in an attempt to assimilate the Highlanders by eradicating all aspect of their culture, including the Gaelic language and their traditional tartan attire. Highlanders are also prohibiting from owning weapons while their clan chiefs have their rights to jurisdiction removed

1790 onwards The Highland Clearances take place. Highlanders are forcibly displaced by their landlords so that the land can be used for sheep farming. Many Highlanders find themselves now living in cities and England, or being sent abroad to Canada, America and Australia

Scots from the upper echelons of society fare better following the demise of Jacobitism and the Act of Union. Middle and upper-class Scots are able to take advantage of opportunities which were previously closed to them. Thousands of Scots, mainly Lowlanders, assume positions of power in politics, the civil service, the army and navy, trade, economics, colonial enterprises and other areas across the nascent British Empire

1790-1815 The Napoleonic Wars bring economic prosperity to the Highlands. An increasing number of young men join the Armed Services with many choosing to settle abroad after being discharged

1800 The Welsh social reformer Robert Owen takes over the running of the cotton mills at New Lanark which become celebrated as models of progressive and socially responsible industrial management

1802 William Symington produces the world’s first practial steamboat using a steam-driven paddle wheel – the Charlotte Dundas – which successfully pulls two 70 ton barges on the Forth and Clyde Canal

1803 The construction of the Caledonian Canal begins bringing much needed employment to the Highlands. It is opened in 1822 and completed in 1847

1807 Henry Benedict Stuart dies in Rome. He is the fourth and final Jacobite to publicly lay claim to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland

1812 Henry Bell runs Europe’s first Europe’s first commercial steamboat service from Glasgow’s Broomielaw to Greenock in the steamboat Comet

1814 One of the most infamous periods in the Highland Clearances takes place on the vast estate of the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland. Residents are brutally evicted from their homes, which in many cases are burnt to the ground, between 1811 and 1821

1815 The kelp fishing industry, an essential source of income for many coastal communities in the Highlands collapses at the end of the Napoleonic Wars following greater access to cheaper continental sources of alkalis. The death of this industry forces many Highlanders to emigrate

1819 Inventor of the steam engine James Watt dies

1820 The Union Chain Bridge across the River Tweed opens and is the first major bridge of its kind to be designed for vehicles. It is the oldest surviving iron chain suspension bridge still in use in Europe

1826 The first modern railway in Scotland opens between Monklands and Kirkintilloch

1831 The first passenger railway in Scotland between Glasgow and Garnkirk in Lanarkshire begins operation

1833 The Factories Act regulates the number of hours young workers are permitted to work per week and bans children under the age of nine from working